The chaps from ASIO were hiding across the road from the Canning Street house in Ainslie. None of the eight women arriving suspected for a moment they were under surveillance, nor did the three hipster blokes leaving: pretty odd given the cameras were probably clicking from a car parked opposite. But then, this was suburban Canberra, 1970.

In those days it didn’t occur to young citizens that they were being spied upon by their government, even if they were self-declared Marxist socialist revolutionaries.

But this ‘new’ group had ASIO particularly worried. They were all sheilas!

It was 6 June1970, the very first meeting of the Canberra Women’s Liberation (CWL) group. Of particular interest to the government spooks was a woman who arrived in a woolly cardigan, wearing dark sunglasses, a short ponytail and carrying a highly suspicious, bulbous shaped hessian bag.

The woman was Julia Ryan. The bag contained her knitting.

Famed for her woollen creations, Ryan was also a prolific writer, diarist and note taker. Thankfully! This legendary Canberra feminist died in 2023, but now a posthumous publication of her of writings, launched last week at the National Archives, provides one of the most informative and compelling insights to the early Women’s Liberation Movement I’ve ever read.

Julia @ Women’s Liberation: Inside the Movement is part history, part diary, part feminist theory, and part love letter to her radical women friends, their daughters and generations of feminists to follow. Ryan herself was the daughter of Australian feminist icon, Edna Ryan.

Just like the birth of the Canberra chapter of Women’s Lib, that had ASIO scrambling for intel, the publication of Ryan’s book is the result of collective action rallied by local author and her dear friend, Biff Ward. The result is history gold.

An emotional Jenny Macklin, former Deputy Leader of the Labor Party and one of Ryan’s ‘Red Fems’ rebel gang, spoke of the enormous task they set themselves back in those heady days; “to determine the intersection between feminism and socialism, patriarchy and capitalism.”

Today we smile at such ambitious theorising, but as Macklin said, back then “That’s (just) the way it was.” As they studied the likes of Mary Wollstonecraft and US feminist Shulamith Firestone, the Canberra Women’s Liberation group came up with an ingenious way to counter media obsession with celebrities.

A central tenet of the women’s movement was no ‘stars’, no leaders or hierarchy. Something Ryan insists the media couldn’t understand, frequently using controversial feminists like Germaine Greer and Kate Millet “to dump on the rest of us”.

So, Ryan and her mates created a fictional woman, Shulamith Wollstonecraft, who “busily signed letters and communicated with the public”. She was a regular correspondent to the Canberra Times! Indeed, one of her most angry letters was in response to RSL action preventing Women Against Rape (WAR) from joining the ANZAC Day march.

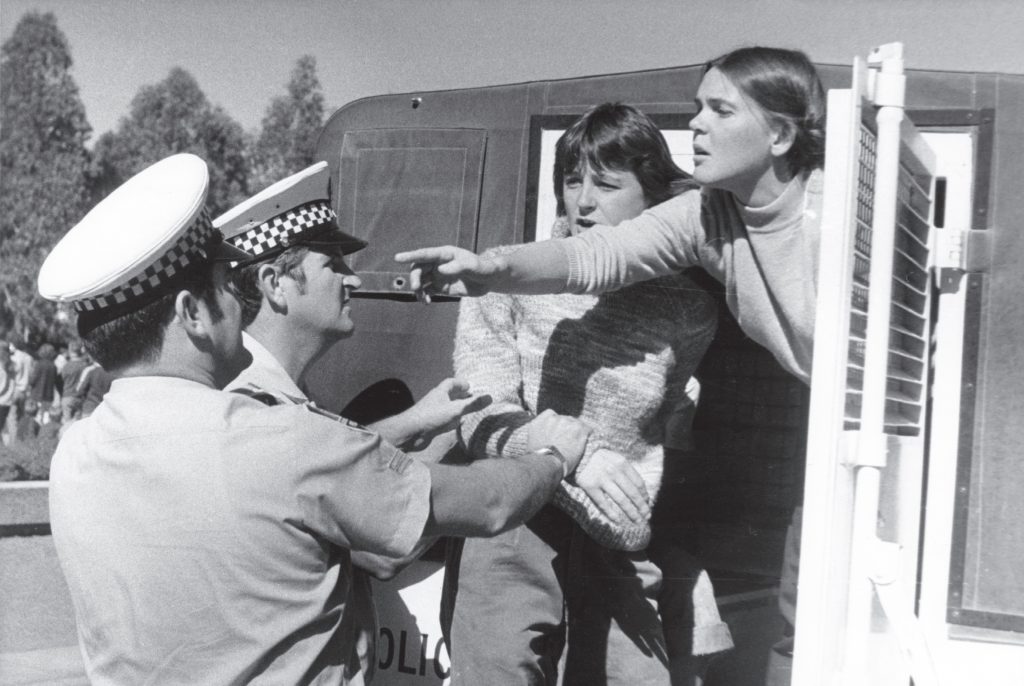

In 1980, 14 young WAR protestors attempted to march up ANZAC parade among the diggers. All of them were arrested.

The following year CWL members joined the WAR protestors and about 100 women committed to march. But according to Ryan, at the last minute “the government panicked”, rushing through a new law which banned anyone from marching if they were not invited by the RSL.

That singular attack on civil liberties tripled the number of women protestors who turned up. “We assembled in a small park, rustling our feet among the red, brown and yellow leaves, three hundred meters from the official march route,” writes Ryan who despite intense anxiety about the action, stood up front, close to Biff Ward who addressed the 300 women gathered.

Ward recalls the police lined up across the street. “Initially we just came up to them, face to face. And we were singing”. Then a most unexpected thing happened. As the women sang “we are gentle, angry women”, Ward noticed some of the police were crying: “There were two or three young men who had tears running down their faces.”

The women formed a circle, then following a silent cue, suddenly darted in different directions to get around the police cordon. As Ryan describes it, “Within minutes the whole organising collective including Biff, were picked off”. A total of 61 women were arrested that day. Fortunately, Julia Ryan wasn’t one of them.

She ran home and did what a great chronicler does – she wrote it all down.

Ryan and the women she writes about entered the 1970’s as young mothers, wives, teachers, workers and university graduates, assuming they were modern, liberated women. They thought the world was theirs. Until they found it wasn’t.

Radical consciousness raising prized open their eyes, recalibrated their thinking and caused a seismic shift in the ground beneath them. Once they saw the sexism and systemic patterns of women’s oppression all around them, they couldn’t unsee it.

Years later, leading feminist Anne Summers looked back on those years saying, “In 1970 I had no idea just how subversive the ideas of women’s liberation would turn out to be.” In her final pages Julia Ryan writes, “We had changed our world – and so very much more.”

Her unique account of those times now lives on as testament to the transformative power of sisterhood when women unite.

Generations of women to follow remain indebted to that legacy.